Canada’s boreal forest became a stable landscape about 7,000 years ago, and in Alberta it once covered the northern half of the province. Wildlife that is rare or endangered other places, including millions of woodland caribou, still thrives there, as do species that have lost much of their original range in North America — grizzly bears, wolverines, lynxes, and wolves. Fire, disease, and insects are an integral part of how the forest was shaped, so the trees are mixed in age and usually less than 100 years old.

Twenty years before I traveled the pipeline route, I lived on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. National forests and other public lands were, and are still, cut and clear-cut there. Groves of western red cedar were cut in the 1950s, leaving stumps that were sometimes 12 feet high. By the 1970s the large old trees were mostly gone, so those stumps were cut a second time to create cedar shakes. A labeled remnant of these magnificent trees stands on Department of Natural Resources land. In the 1990s I spent time with a crew of “cedar rats” who were cutting the stumps, now less than six feet tall, a third time. On my trips to photograph them, their community, and their workday, I passed miles and miles of clear-cuts. The visible land scars engendered an ominous sense of danger that simply became part of those field days.

I recognized the feeling when I arrived in northern Alberta and saw what surface mining of tar sands does to the land. It completely removes the complex ecosystem of the forest, diverts rivers and streams, and drains or excavates wetlands.Hydraulic shovels and mammoth trucks remove the tar sands — 2 metric tons of sand are removed to produce one barrel of oil — from deep open pits. One effect of this land clearing is the displacement of birds and wildlife. Black bears are shot when they wander into oil sands workers’ camps to scavenge, and the Canadian government has proposed shooting and poisoning wolves as a remedy for the woodland caribou’s loss of habitat.

As in the Washington clear-cuts, birds and wildlife in the boreal forest are driven out or killed. This violence to the land seems contagious, and its reach finds its extension to human life in a long legacy of sex trafficking and rape endemic in the mining industries. It continues in the oil field man-camps, and it plagued communities where Keystone I workers bunked. Sexual violence looms as one more significant threat of the Keystone XL.

Fort McMurray’s population boomed with the development of oil sands starting in the 1960s. On May 1, 2016, a fire began southwest of Fort McMurray and burned out of control until July 5. The fire reached Fort McMurray on May 3. Large parts of the town were evacuated, and entire neighborhoods were destroyed. A wildfire researcher called that fire “consistent with what we expect from human-caused climate change.”

I was in Fort McMurray one year after the fire. The Beacon Hill neighborhood had lost more than four hundred homes, and rebuilding activity was intense. The neighborhood looked new again, but the forest that edged the neighborhood along the Hangingstone River stands charred.

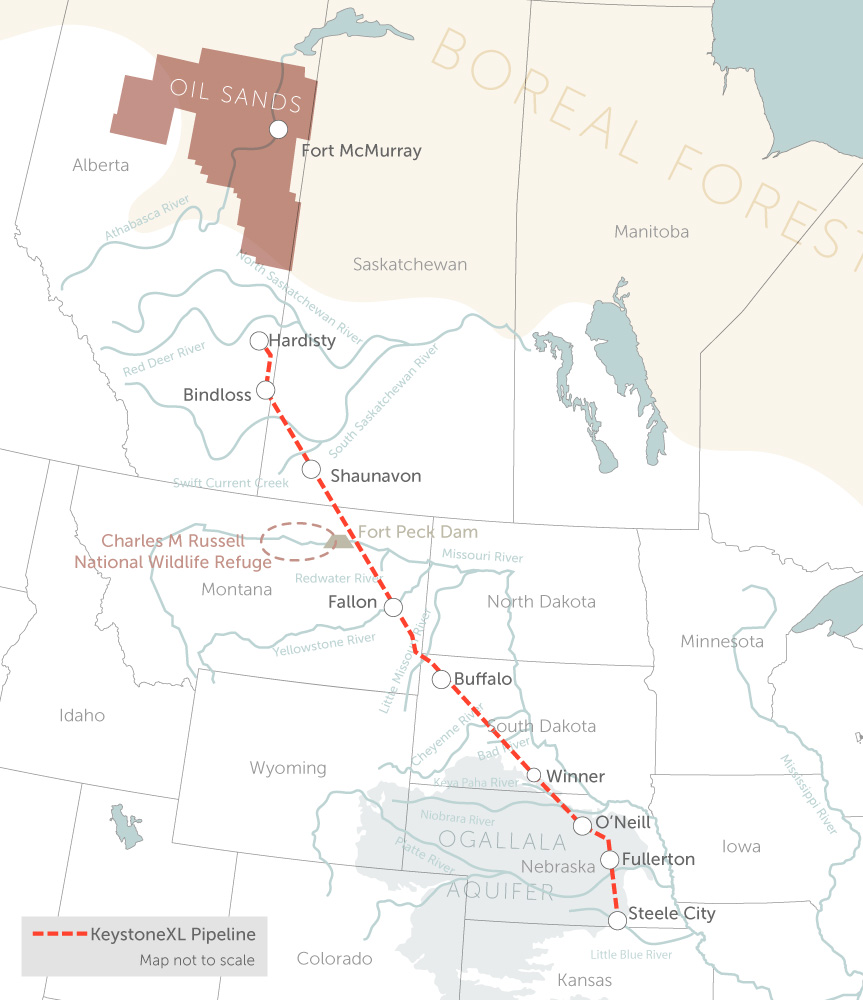

When I mapped out my trip, the list of named large rivers — Red Deer, Saskatchewan, Cheyenne, Yellowstone, Missouri, Niobrara, and North Platte — was impressive. What I was not prepared for was the multitude of small rivers and tributaries this pipeline would need to cross. In the United States that number is well over 1,000, including intermittent, perennial, and ephemeral streams; small tributary creeks; and major rivers. In addition, there are correspondingly large and small rivers in Alberta and Saskatchewan and abundant sloughs that wildlife, ranchers, and groundwater replenishment rely on. From Hardisty to Steele City my trip involved looking at water along the way, staying within range — and always downstream — of the proposed pipeline.

Leaving the tar sands country and going south from Hardisty, I wandered the least traveled roads I could find to Steele City. It was a quiet and spacious trip through the spaces in between the Alberta refinery and the Steele City pumping station.

On a barely two-lane dirt road in Holt County, Nebraska, I stopped along the Niobrara River. It is a very isolated stretch of road, and I didn’t see any people or cars, but as I walked I could hear children laughing. I finally found them in the river — a dozen girls in the right place on a very hot day. Over and over they caught the current, yelled at each other to get out of the current, and swam back upstream to start again. Soon after, on the last day of my trip, I walked for hours along the Platte River at the Rowe Audubon Sanctuary. In spring, up to 500,000 sandhill cranes, a much smaller number of endangered whooping cranes, and a multitude of other migratory birds congregate along an 80-mile stretch of the river, some on their way to nesting grounds along the migratory route to Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Alberta. On a weekday in June, I was the only one there, and there were very few birds of any kind.

To see those girls in the Niobrara oblivious to any threat but the current and to be along the Platte midday without the cacophony of bird life seemed to underline what this pipeline put at risk. The pipeline would have filled no need but instead brought the threat of abuse to the communities and the land it would have passed through. It threatened all the delicate, the hard-used, and the filled-with-life spaces in between.

The failure of this project was a great victory for the coalition of ranchers, farmers, tribes and other landowners in Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska who doggedly fought its construction. As Bill McKibben points out in his opinion the fight against other tar sands pipelines simply shifted to new ground.

Back to Spaces in Between